New Straits Times, 26 September 2010

Art: The Warrior Painter

by Rachel Jenagaratnam

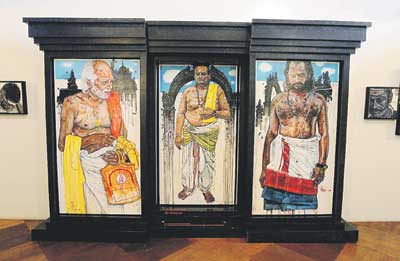

Anurendra says this collection has been a joyful exercise. Seen here, This Is Where We Live, oil on canvas

Anurendra Jegadeva tells RACHEL JENAGARATNAM about his latest art works that have taken two years in the making

“IT’S nice and it’s sad as well. They’re like your children, right? I’ve lived with them for two years,” says Anurendra Jegadeva, smiling.

The artist is describing his bittersweet goodbye with his paintings, which debuted at his latest solo exhibition, My God Is My Truck — Heroic Portraiture From The Far Side Of Paradise, at Wei-Ling Gallery recently. It comes three years after his last solo exhibition, Unconditional Love, and his 15 new works have been long anticipated.

“My wife is over the moon-lah. She can finally see light coming through the house,” jokes the artist about the clean-up at his home studio.

However, like a proud father, Anurendra says it has been “a joyful exercise” watching these artworks develop. And, like any doting parent, Anurendra has given them the best possible start to life: A good education, a worldly outlook, and, he’s even dressed them up in bright, jubilant colours to facilitate a good first impression.

They’ve got good manners too. Anurendra’s paintings greet you before you even set foot in the gallery, and once inside, you’ll see the rest lined up, eager for your inspection.

There are life-sized paintings of Hindu priests encased in black aluminium frames that resemble shrines found in the inner sanctum of temples, the richly coloured title painting of the exhibition at the far end of the gallery, Beano and Dandy characters on the same floor as a portrait of the artist’s mother, resplendent as the queen, and the artist’s aunts — depicted like pin-up comic book heroines — situated at the very top floor.

“It’s a wonderful hang. I must say it was pushed by the space dynamics as well,” says the artist.

The space dynamics he refers to is, of course, Wei-Ling Gallery’s unique split-level exhibition space and the gallery’s architectural properties (once ravaged by a fire and cleverly restored to depict this history).

Anurendra explains how audiences can read the exhibition from the ground floor up, or reversely, work their way downward.

He also interprets the themes that pervade each level. The ground floor can be seen as the artist’s view of the present. The first floor presents works that illustrate — within postcolonial parameters — how he has arrived at this point and the top floor boasts images that refer to his Sri Lankan heritage.

Whilst each theme is autonomous and capable of standing on its own, they do co-exist harmoniously. And, it’s precisely the notion of co-existence that functions as one of the key themes of the show, alongside the artist’s suggestion that we are on a constant search for heroes.

Indeed, Anurendra has transformed the space into a veritable gallery of icons.

There are political figures and pop stars in the fray of subjects and these disparate elements are joined by the artist’s own personal history.

The artist’s family members, for instance, are scattered throughout the exhibition, and even his pet pug, Mushu, stars in an artwork (V Is For Vigilant from his Alphabet For The Middle-Aged Middle Classes).

The multiple themes correspond to Anurendra’s own multifaceted existence. He wore the hat of an art writer for about a decade, lived the migrant experience in Australia, and more recently, was a curator for a major art gallery in Kuala Lumpur.

And whilst these personal themes often creep into Anurendra’s work, the artist finds no greater joy than when he is making art. As he eloquently states in the introduction to his essay in the exhibition’s accompanying publication: “I am happiest when I am painting in my studio. That is why I make these things — making them makes me happy. Once I was a writer, then a curator, intermittently both, agitated and frightened, often confused, too fat, too sweaty, mostly conciliatory. And always tired.

“But when I am painting, I too am a warrior. I am brave and honest (and thin) — I see my version of the world clearly and am able to engage with it, to joyfully deconstruct it, to shamelessly indulge in the craft of painting.”

Indeed, Anurendra admits to having been preoccupied with “pushing painting’s boundaries” in making this batch of works. Evidence of this can be seen in the artist’s unorthodox canvases, where pieces have been cut out and reassembled like in Prophecy, a work featuring portraits of our six Prime Ministers to date whose first names spell R-A-H-M-A-N.

Then, there are the 27 collages encased in Perspex boxes titled Alphabet For The Middle-Aged Middle Classes.

Torn pages or single elements from the artist’s actual childhood storybooks are married with his illustrations to form collages that wittily reinterpret the alphabet with flavours of the 21st Century. C is for Change has a profile of Barack Obama, N is for Neighbour shows Hazel, the Arab, nestled amidst wholesome Enid Blyton characters, and G is for Godhead offers us an image of the Lord Ganesha.

Still, there is some continuation from previous endeavours and those familiar with the artist’s oeuvre will be able to discern the hallmarks of his style.

“I don’t work in series,” Anurendra professes. Naysayers may pick on this, but the artist attests that whilst his staples — “humour, popular culture, and the figure, of course” — will always be there, his aesthetics have resisted stagnancy.

“The storytelling medium,” he points out, has also gotten more fluid. More complex too, as the subtle nuances in each work is purposeful and laden with meaning. The artist’s Red Dot Brigade, for example. These portraits of 20 Indian men form the congregation that flank the three Hindu priests and each individual bears a red dot on his forehead, a reference to both religion and the commercialism in his line of work (“sold” artworks in galleries are identified by a red dot on the artwork’s label).

Complexities aside, it will no doubt be easy to appreciate Anurendra’s beautifully crafted paintings and to find something to engage with on an individual level, whether it is shared postcolonial baggage with the artist or a sense of familiarity in viewing some of the figures, most of whom are based on real people.

Anurendra says this exhibition is about fitting in and he calls himself an “everyman”. I reckon this is true. An exhibition that manages to feature Hello Kitty, Saddam Hussein, and Loga from The Alleycats in one fell swoop, displays an unquestionably versatile and wide-ranging observation of the world we live in today. And, it is one that is inclusive and gives us room to co-exist.