Therapy and Paradox in Yau Bee Ling’s Painting

by Anurendra Jegadeva

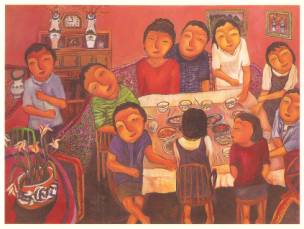

With their tapestries of vibrant colour and vivacious form, the art of Yau Bee Ling has generally been celebratory. From the earliest naïve family portraits, the later abstract still-life’s and right up to the current Portraits of Paradox their expression has always been almost fiesta-like.

For all their celebratory aspects, however, her artwork is never without its opposite, namely a sense of the wistful and sad; of regret and a deep sense of loss.

Flashy colours are counterbalanced by abrupt often intentionally awkward forms – family members, empty wine glasses, arrogant rambutans or meek mangosteens – they all have specific personalities and characteristics all their own.

In the earliest Family Series works, the faces are drawn so as to be fleshy and child-like in their pristine directness but they also feature a tense brittleness that is the opposite of naiveté. Her Malaysian context is expressed within the confines of race, class, tradition, clan personal family histories.

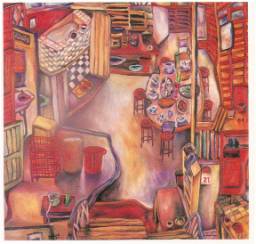

With the Moving Out Moving In works, made during her Rimbun Dahan residency, the artist begins to pull away from the autobiographical.

She begins with the expulsion of the human actors from the picture planes – but never completely.

Their presence is felt just outside the central compositions and impossible perspectives as if they only left a moment ago.

Sometimes they literally dance around the edge of the parameters of her canvas.

The paintings themselves become a part of a narrative which lives in their titles. The still-life of fruit in Gifts from the In-laws or the parade of beautiful objects in Make-up Set on Red Table and Red Couch in Living Room all combine to provide a portrait of their owner… more often than not the artist herself.

In Portraits of Paradox, Bee Ling returns to the figurative, but now departing from the obviously autobiographical for the purely paradoxical.

Employing her signature complex and dense configuration of subjects/objects, the artist searches for a generic aesthetic stripped of personal specificity to explore the human condition at large.

She abandons the softer romanticism of nostalgia and beautiful objects in luscious colour which inhabited her older bodies of work for a constrained palette of muted greys and blues and pinks and greens.

The large heads like Arbitrary Ruler I as well as the group portraits (ie Mass Gathering) boast a weave of heads within the head. Their form is derived from random coloured patterns in ceruleans, olive greens and oranges, their features shaped by the instinctive play of dark marks.

In the large portraits, the artist’s inspiration remains her loved ones – the people she has interacted with as a daughter, sister, wife, daughter-in-law, mothers, friend and always – artist.

Within the babble of voices that call out from these paintings – some are quiet, sad, pensive, and angry while others are deceitful, proud and suspicious and resentful.

Their noise is audible.

Pride with its red fore-corners is autobiographical in that it examines gender issues trough the trials of spousal and maternal conflict as well as larger issues that affect women within and outside the artist’s own immediate experience with relation to race, class, religion and always family.

Likewise, The Arbitrary Rulers refer to a host of possible protagonists – her father, her partner, her child … and ours.

In Immortalised Ruler the artist pays obvious homage to her father while she carefully and uncomfortably confronts the nature of their relationship – the universal patriarch or father-figure is expressed through the tilt of the head which is stiff; the gaze of the eyes which are piercing, as well as the stubborn jaw-line.

The ambitious group portraits’ like Mass Gathering and The Meeting are more obvious commentaries on society. These works dialogue directly with the state of the art movement, of institutions as well as arts administrators, curators, patrons, dealers and her fellow artists while offering broader references to current events like street demonstrations, always returning to the immediate predicament of the time-honoured tensions of domesticity and family.

These are the artist’s people but they are ours too.

For Bee Ling her art has always been a form of therapy – a way for the artist to resolve the external and accept the internal.

Bee Ling is a young Malaysian woman from a traditional Chinese family, who as a wife and mother also holds dearly to these traditional cultural values. All these factors, perpetuated by the socio-economic-political realities of modern Malaysia has meant that – like most Malaysian artists – issues of self and identity invariably, at least as a starting point, dominate her aesthetic.

Their therapeutic quality, however, are thankfully overshadowed by a serious commitment to their aesthetics prowess.

Portraits of Paradox possesses both a sophisticated sense of design and an exciting play of space which are the hallmarks of credible painting which has persevered since the early works.

These are Bee Ling’s most expressive and gestural works to date even if they are not her easiest. The overlay of short straps of colour that make up her `heads’ show her

thorough conceptual division of the condition of light and order while addressing personal as well as universal narratives.

In these most recent paintings, Bee Ling completely superimposes the heads across the picture plane. She densely paints these portraits with a full range of colours in muted pastel hues and with more urgency than ever before.

The crowds of actors remain trapped or confined in their picture plane but their interaction all point towards a coexistence of things and persons which adds to our consciousness of our own existence.

Giving new life to old patterns, Bee Ling is more generic than ever before… she doesn’t beat you over the head with specific objects or persons to tell her specific story.

Rather, with these portraits, she lets things happen in the course of personal associations.

As a repository of thoughts and feelings her paintings symbolize a human ethic, concern and consciousness rarely encountered in modern life.

Anurendra Jegadeva is a writer artist and curator who has lived and worked in Malaysia and Australia. He is currently the Senior Curator at GALERI PETRONAS, Kuala Lumpur, a premier contemporary art space owned by the national petroleum company, PETRONAS.