New Straits Times

Delicious combination

by Lucien De Guise

INSTEAD of doing Sudoko this weekend, how about stretching your mind by compiling a “Czech list” of cheerful happenings? It will probably be a short one.

The path of history has not been smooth for the Czech people. Over the centuries they had been overrun by Mongols, Ottomans, Austrians, Nazis and Soviets. Kafka is their famous cultural spokesman, and he wrote in German.

But things seem to be improving lately, although maybe not for religious evangelists of any sort: The Czech Republic has Europe’s second lowest number of believers in God.

Among the recurring bright spots over the years are glass (from Bohemia) and photography (by Jan Saudek and others).

Now the two have come together, in a deliciously monochromatic fashion, at the Wei-Ling Gallery within the polychromatic environs of Brickfields. The Glass Gellages exhibition ends April 30.

This corner of Kuala Lumpur is a long way from the sombre, gloomy beauty of Prague, but then so is the photographer. Michal Macku avoids big city life in the Czech Republic. He enjoys contemplation and macrobiotics instead.

I always hope to meet artists whose first calling was not to be a PR man. Macku has the withdrawn energy of a Kafka, but he manages to smile as well.

The most exciting aspect of his work is not his ability to perfect established art forms. He is a quiet innovator. This is something of a national tradition, although the nation doesn’t always get the most famous inventions. Instead, it’s the quiet revolution of contact lenses. Nothing showy. In fact, it’s usually invisible stuff that might fall in the basin and never be found again.

Some of Macku’s works are the same. When I see them on a brochure or website, I am not really seeing them at all.

This is one of the few media that can only be appreciated in the real world. His works with glass are sure to make an impression. There were already numerous “sold” stickers attached to these limited editions when I saw them, and that was the day after the launch.

Macku also works in a different sort of medium, which at first sight looks like standard silver-gelatin prints. Being the highly original sort of person he is, this is just an illusion. He has given the process a name: “Gellage”. It’s complex and involves loosened gelatin.

The subject matter is also likely to alarm. I’ve had a lifelong anxiety about the type of high-precision anatomical photography that Victorian enthusiasts relished. Its modern descendants are on view in the windows of medical practitioners who operate from shoplots in, mainly, Petaling Jaya.

The Victorians had to make do with black and white, rather than multi-mega-pixel renderings, but the pioneers made up for this by recording every conceivable deformity in loving detail.

In the 20th Century, my least-favourite photographer went one step further. Joel-Peter Witkin put together vignettes of body parts in artfully arranged fashion that were far more disturbing than anything by the more famous shock-tacticians of the past two decades.

Macku’s prints head a little way in this direction by scraping away parts of the image. A complete GQ model might therefore appear to have had his arm or face scratched off. It’s dramatic and exquisitely executed and as inviting as a rainy night of Kafka recitals under a railway bridge in Prague.

Like a giant Kafka-esque cockroach, I found myself wanting to scurry away from the “Gellage” section and back to the security of the “Glass Gellages”. Macku’s work in three dimensions is both astonishing and appealing.

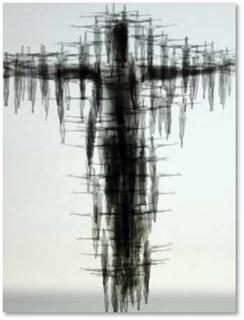

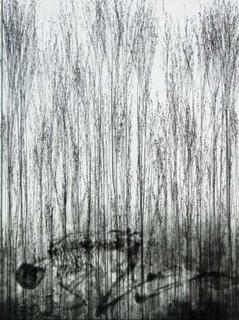

Although glass is not always considered the warmest and most inviting of materials, in this artist’s hands the transformation is complete. His creations are composed of numerous layers of glass, each one with an image printed photographically on it.

When all layers have been put together, the result is a sandwich of glass in which shades of grey and black float in a mysterious and disembodied manner. For objects that are just under 30sqcm, with a depth of about four centimetres, they have a presence that is far in excess of their size.

His Glass Gellages work as sculptures, photographs and glass. It’s not often you encounter a three-in-one of such promise. They can be placed on a plinth, a shelf or a wall and they resonate with the quality of photographs that are both there and not there.

They are a supremely tasteful alternative to those digital slideshows that operate as a freedstanding display. No batteries or AC sources are needed for Macku’s Glass Gellages.

It’s rarely that I encounter an art form that electrifies without electricity. Macku’s works in glass are really worth a look. It’s not just the technique that is so bewitching, although this is an important factor; it’s a bit like being in the mid-19th century and seeing a photograph for the first time. The contents of the glass are just as significant.

When I mentioned to the artist that there seemed to be something for everyone, he looked doubtful. He creates what pleases him, rather than the public. His personal taste appears to veer between the most uplifting scenes of grasses reaching to the sky and figures that might be Christ on the cross.

There is much ambiguity in them, but also a total delight in the two media that he has combined.